Sumerian Greeting Builder

The oldest known written greeting comes from a 4,500-year-old Sumerian tablet discovered in Uruk. It reads "É-gi-a-ni-ka-ri-ma" meaning "May you live forever."

Build Your Own Ancient Greeting

Explore how the components of this greeting combine to form a meaningful phrase.

When you say "hello" or "namaste," you’re joining a tradition that stretches back millennia. Scholars have pieced together the very first words people used to acknowledge each other, and the evidence points to a surprisingly poetic phrase from ancient Mesopotamia. Below we unpack how that phrase was discovered, what it actually says, and why it still matters today.

Quick Takeaways

- The oldest documented greeting comes from a 4,500‑year‑old Sumerian tablet.

- It reads "É‑gi‑a‑ni‑ka‑ri‑ma" meaning “May you live forever.”

- Similar early salutations appear in Egyptian, Indus, and Vedic sources.

- Understanding these greetings reveals how early societies valued hospitality and divine favor.

- Modern greetings still echo the wish for well‑being found in ancient words.

What Counts as a Greeting?

Before we label something the "oldest," we need a clear definition. A greeting is a brief utterance or gesture used to acknowledge another person's presence, often expressing goodwill or respect. It differs from a full‑blown prayer or proclamation because it’s meant for everyday interaction, not ceremony.

Researchers therefore focus on short, repeatable phrases found in everyday contexts-like letters, trade records, or personal inscriptions-rather than epic poetry or royal decrees. The phrase we’ll discuss fits this bill: it appears on a commercial tablet, not a king's proclamation, suggesting it was part of routine communication.

Discovery of the Sumerian Tablet

In 1924, archaeologists excavating the ancient city of Uruk, a major Sumerian civilization hub, uncovered a baked‑clay tablet embossed with cuneiform signs. The tablet, cataloged as “MS 345,” dates to around 2400 BCE, placing it squarely in the Early Dynastic III period.

The text is a simple business receipt, noting the delivery of barley. At the bottom, a short phrase-"É‑gi‑a‑ni‑ka‑ri‑ma"-was added in the scribe's hand. When scholars translated it, they found the meaning: “May you live forever.” This sentiment, expressed in a single line, functions exactly like a modern "hello" paired with a wish for health.

How the Phrase Was Decoded

Deciphering cuneiform is a meticulous process. Researchers compare sign shapes to known lexical lists, such as the Wells‑Jaggar sign list, and cross‑reference with bilingual tablets (e.g., Sumerian‑Akkadian). The key signs in our greeting are:

- É - “house” or a formal prefix.

- gi‑a - “to live.”

- ni‑ka‑ri‑ma - a verb form meaning “may you be.”

Putting the pieces together yields the literal “May you (the person) live forever in my house.” Over time, the phrase shed its literal house reference, becoming a concise well‑wish.

Other Early Greetings Around the World

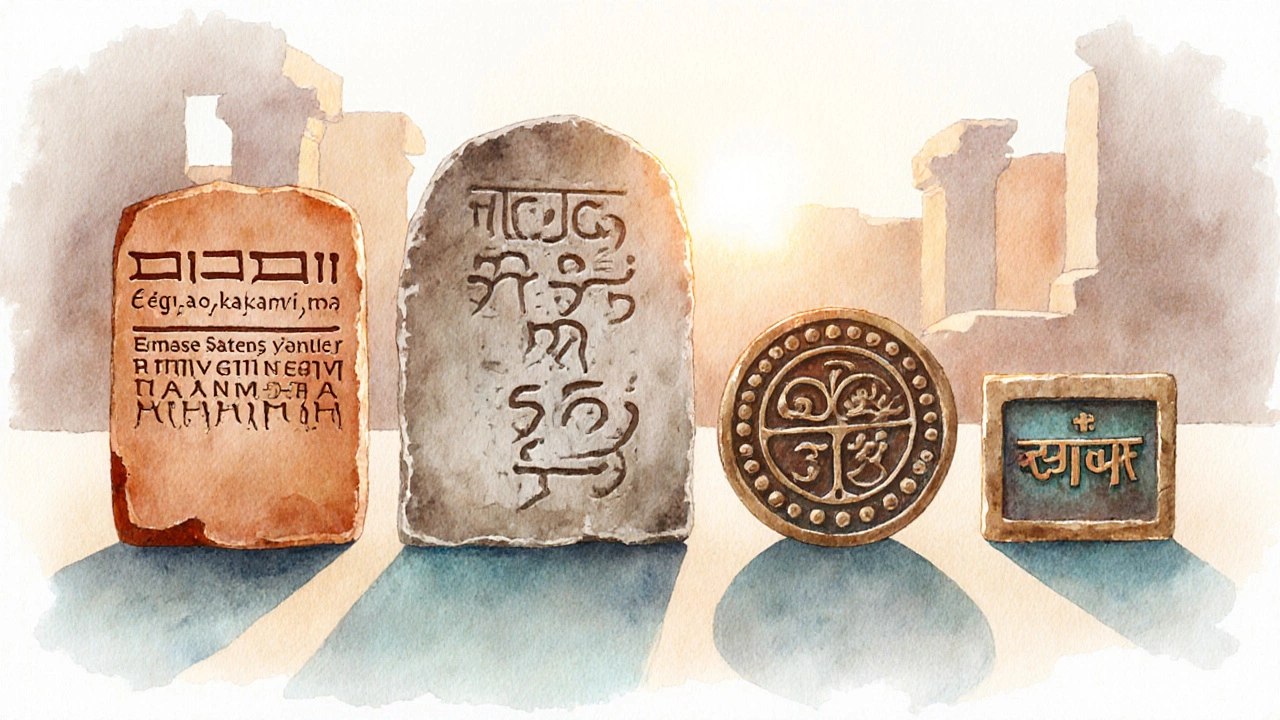

While the Sumerian example holds the title for the oldest surviving written greeting, parallel traditions emerged elsewhere. Below is a brief look at three other ancient cultures that left behind salutations on stone, pottery, or papyrus.

| Culture | Approx. Date | Language | Greeting Text | Literal Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sumerian (Mesopotamia) | ~2400 BCE | Sumerian | É‑gi‑a‑ni‑ka‑ri‑ma | May you live forever |

| Ancient Egyptian | ~2100 BCE | Egyptian | 𓂋𓈖𓏏 (ren‑i‑t) | May you be well |

| Indus Valley | ~1900 BCE | Undeciphered | Standardized seal motifs (interpreted as greeting symbols) | Good wishes for safe travel |

| Vedic (Ancient India) | ~1500 BCE | Sanskrit | नमः (namah) | I bow to you |

The Egyptian example comes from a tomb inscription where a priest writes "𓂋𓈖𓏏," interpreted as a standard well‑wish. In the Indus Valley, no actual script has been decoded, but the consistent use of a particular seal motif on trade goods is thought to convey a greeting‑like intention-essentially a visual "welcome."

In the Vedic tradition, the word namah appears in the opening of many hymns. Though formally a bowing gesture, it functions as a greeting, especially in the phrase "Om namah shivāya"-"I bow to Shiva."

Why the Oldest Greeting Still Matters

Understanding the ancient salutation does more than satisfy trivia. It shows that early societies already recognized the power of a brief, positive exchange. The wish for longevity reflects a universal human hope: safety, health, and continuity.

Modern psychologists link greeting rituals to social bonding and stress reduction. The ancient "May you live forever" is an early form of what today we call a "positive affective greeting." By tracing its roots, we see that the social glue of hospitality has been essential for cooperation, trade, and community building since the dawn of writing.

Furthermore, the discovery reinforces the value of interdisciplinary work-archaeology, linguistics, and digital imaging all contributed to reading a tiny crumb of clay. As more tablets are digitized, we may uncover even older examples, pushing the timeline further back.

How to Spot Early Greetings in Everyday Artifacts

If you ever visit a museum, look for these clues:

- Repetitive short phrases on everyday objects like receipts, letters, or trade seals.

- Accompanying symbols that suggest goodwill, such as a lotus (Egypt) or a cattle motif (Mesopotamia).

- Placement near the end of a text block, indicating a closing remark rather than a narrative.

When you spot such features, you’re essentially seeing a snapshot of how ancient people greeted each other.

Mini FAQ

What is the exact wording of the oldest known greeting?

The phrase is É‑gi‑a‑ni‑ka‑ri‑ma, which translates to “May you live forever.”

Where was the tablet containing this greeting found?

It was uncovered at the ancient Sumerian city of Uruk in present‑day Iraq.

Are there older greetings that haven’t survived?

Yes. Many early societies used oral greetings that left no written record. The clay tablet is the oldest *documented* example.

How do scholars translate cuneiform greetings?

They compare sign shapes to known lexical lists, use bilingual tablets for reference, and apply contextual clues from surrounding text.

Do modern Indian greetings trace back to these ancient salutations?

Indian greetings like "namaste" come from Vedic Sanskrit, a language that evolved around the same era as the Sumerian example, showing a parallel development of respectful salutations.

Takeaway for Today’s Readers

Next time you say "hello," remember you’re echoing a 4,500‑year‑old wish for long life. That simple phrase links us to farmers in Uruk, priests in Thebes, and sages in the Indus Valley. By recognizing the depth behind our everyday greetings, we can appreciate the timeless human desire to acknowledge each other with goodwill.

And if you ever stumble upon an ancient tablet or a weathered seal, ask yourself: could this be an early "hi"? The answer might just surprise you.

oldest greeting continues to remind us that behind every culture’s language lies a shared hope for another’s well‑being.