Jathi Beat Counter

Count Your Beats

Your Results

When you watch a Bharatanatyam performance, the footwork doesn’t just look precise-it feels like a heartbeat. Every tap, stomp, and glide follows a hidden rhythm structure called a jathi. These aren’t random steps. They’re the building blocks of rhythm in this ancient dance form, and there are exactly five of them. Understanding these jathis isn’t just for dancers-it helps anyone appreciate why Bharatanatyam feels so deeply musical.

What Exactly Is a Jathi?

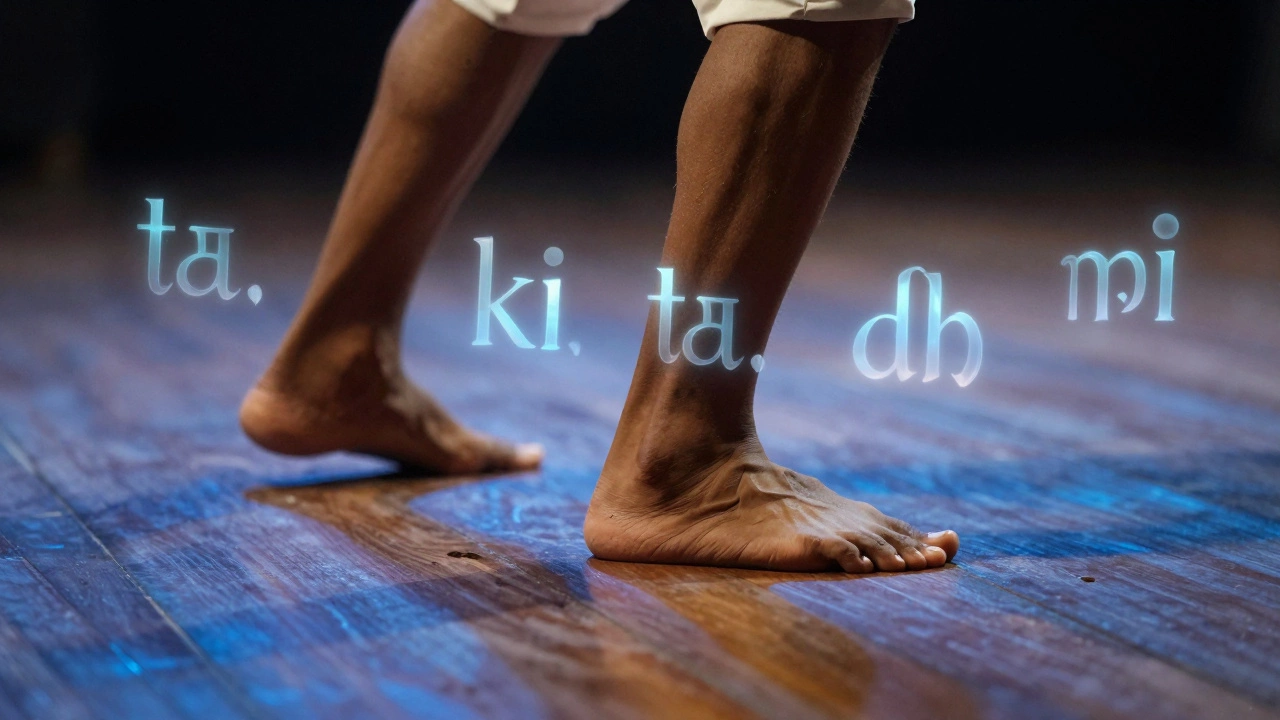

A jathi is a fixed sequence of syllables that represent specific foot movements and rhythmic patterns. Think of it like a drum pattern, but instead of using drums, the dancer’s feet speak the rhythm. Each jathi has a set number of beats and a specific arrangement of sounds like ‘ta’, ‘ki’, ‘ta’, ‘ka’, ‘dhi’, ‘mi’, and so on. These syllables are part of a spoken language called solkattu, which is used to teach and practice rhythm in Indian classical music and dance.

Unlike Western music, where rhythms are often counted in 4/4 or 3/4 time, Bharatanatyam uses complex cycles called tala that can stretch to 7, 9, 11, or even 14 beats. Jathis are the actual patterns that fill these cycles. They’re not just for show-they’re the skeleton of the dance’s rhythmic expression.

The Five Jathis of Bharatanatyam

There are five core jathis, each with a unique structure and feel. They’re taught in order, starting from the simplest to the most complex. Here’s what each one looks like:

- Chatusra Jathi - This is the most basic. It’s built on groups of four beats. The syllables go: ta-ki-ta-ka. It’s steady, clear, and easy to follow. Think of it like walking in time-each step lands exactly on the beat. This jathi is often used in introductory pieces and helps dancers build control.

- Tisra Jathi - This one uses groups of three: ta-ki-ta. It feels lopsided at first because three doesn’t divide evenly into the common 8-beat cycles. Dancers have to adjust their timing to make it flow. This jathi is common in slower, more lyrical sections and adds a gentle, rolling feel to the performance.

- Khanda Jathi - Made of five beats: ta-ki-ta-ka-dhi. It’s the first jathi that feels truly complex. Five beats don’t fit neatly into standard talas, so dancers learn to stretch and compress their movements to match. This jathi is often used in the middle of a piece to create tension and surprise.

- Misra Jathi - Seven beats: ta-ki-ta-ka-dhi-mi-ka. This is where things get intricate. Seven is an odd number, and it’s rarely used in Western music. In Bharatanatyam, misra jathi creates a sense of forward motion, almost like a wave that never quite settles. It’s used in advanced compositions and requires strong muscle memory.

- Sankirna Jathi - Nine beats: ta-ki-ta-ka-dhi-mi-ka-ta-dhi. This is the most demanding. Nine beats feel almost impossible to count at first. Dancers train for years to execute this smoothly. It’s often reserved for climactic moments in a performance, where the dancer’s precision and stamina are put to the test.

How Jathis Connect to Tala and Nadai

Jathis don’t work alone. They’re always tied to a tala (rhythmic cycle) and a nadai (subdivision). For example, a jathi might be played in a 7-beat tala called Sankeerna Matya, and each beat could be subdivided into three (tisra nadai) or four (chatusra nadai). That means one jathi can be performed in multiple ways depending on the context.

Take the chatusra jathi. In chatusra nadai, each beat splits into four, so the same pattern becomes 16 subdivisions. In tisra nadai, it becomes 12. That’s why two dancers can perform the same jathi and sound completely different-they’re using different subdivisions. This flexibility is what makes Bharatanatyam so rich.

Why These Five Jathis Matter

These five jathis aren’t just a list-they’re a complete system. Every complex rhythmic pattern in Bharatanatyam is built by combining or varying these five. Even the most advanced compositions, like the thillana (the fast, energetic finale), are made of layered jathis. A dancer doesn’t memorize hundreds of patterns. They learn these five, then learn how to mix, stretch, and reverse them.

For students, mastering jathis means learning to listen differently. You start hearing rhythm not as a background beat, but as a language. The footwork becomes a conversation between the dancer and the mridangam player. You begin to anticipate where the next accent lands-not because you counted, but because you feel it.

How Jathis Are Taught and Practiced

Learning jathis starts with speaking them aloud. Students sit with their guru and repeat the syllables, clapping or tapping their knees. Only after they can say them perfectly do they move to the floor. The goal isn’t speed-it’s accuracy. A single misplaced syllable throws off the whole pattern.

Modern dancers often use metronomes or apps to practice timing, but traditional training still relies on the guru’s voice. The rhythm is passed down orally, like a song. This is why Bharatanatyam has stayed so consistent for centuries-it’s not written in books. It’s lived in the body and the ear.

What Happens When Jathis Go Wrong

If a dancer messes up a jathi, the whole performance stumbles. The mridangam player will pause or change their pattern to match the mistake. The audience might not know why, but they’ll feel something’s off. That’s the power of rhythm-it’s invisible until it breaks.

One famous dancer from Chennai once said, ‘A perfect jathi is silent. You don’t hear the steps-you hear the space between them.’ That’s the goal: to make the rhythm feel natural, like breathing.

Where to Hear Jathis in a Real Performance

Listen closely during the varnam section of a Bharatanatyam recital. That’s where the dancer and percussionist engage in a rhythmic duel. You’ll hear them trade jathis back and forth, each one more complex than the last. The thillana is another great place-fast, flashy, and full of layered jathis. If you’re watching a live show, try counting the beats. You might not get it right, but you’ll start to feel the structure beneath the movement.

Modern Changes and Challenges

Today, some dancers blend jathis with Western rhythms or electronic beats. While this opens new creative doors, purists argue it dilutes the tradition. The five jathis have been unchanged for over 200 years. They’re not just patterns-they’re cultural anchors.

Still, the core remains. Even in fusion performances, if the jathis are gone, it’s no longer Bharatanatyam. It’s something else.

Final Thoughts: More Than Steps

The five jathis are the soul of Bharatanatyam’s rhythm. They’re not just footwork-they’re the language of time. Learning them means learning to think in pulses, to move with precision, and to listen like a musician. You don’t need to dance to appreciate them. Just watch. Listen. Feel the space between the beats. That’s where the magic lives.

What are the five jathis in Bharatanatyam?

The five jathis are Chatusra (4 beats), Tisra (3 beats), Khanda (5 beats), Misra (7 beats), and Sankirna (9 beats). Each is a fixed sequence of syllables representing footwork patterns, forming the rhythmic foundation of Bharatanatyam.

How are jathis different from talas?

Jathis are the actual rhythmic patterns made of syllables like ‘ta-ki-ta’, while talas are the larger rhythmic cycles-like 7-beat or 14-beat loops-that hold those patterns. Jathis fill the tala, like words fill a sentence.

Why are jathis spoken aloud before dancing?

Speaking jathis aloud helps dancers internalize the rhythm before moving. The syllables act as a mental map. You can’t dance a jathi correctly if you don’t know its sound first. This oral tradition ensures precision across generations.

Can jathis be used in other Indian dance forms?

Similar rhythmic patterns exist in Kuchipudi and Odissi, but the specific five jathis are unique to Bharatanatyam. Other forms have their own systems, like the ‘tihai’ or ‘kavittam’, but the jathi structure as defined here is exclusive to Bharatanatyam’s tradition.

How long does it take to master jathis?

Basic jathis like Chatusra and Tisra can be learned in months, but mastering all five-especially Sankirna-takes years. Many dancers spend 3-5 years just on rhythm before moving to complex expressions. It’s not about speed; it’s about accuracy and muscle memory.