Ghazal Structure Checker

Check if your poem follows the essential rules of a ghazal: at least 5 couplets, same radeef at the end of each line, and consistent qaafiya rhyme.

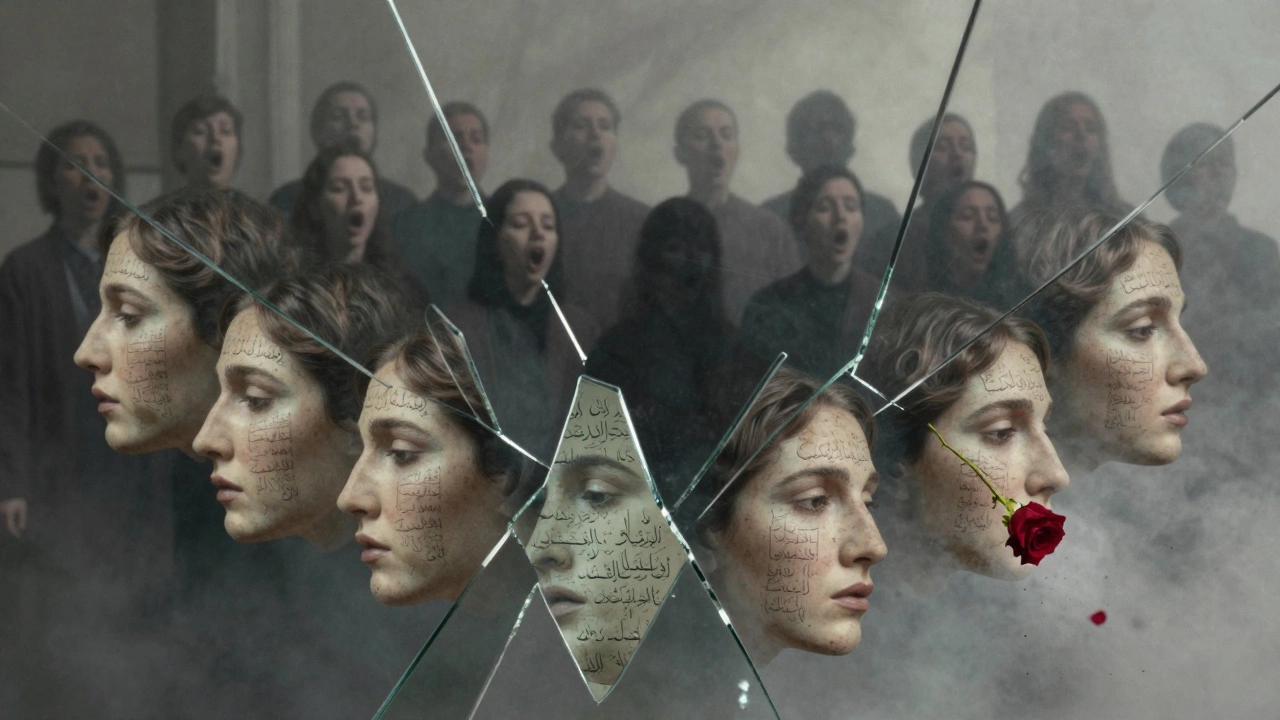

A ghazal isn’t something you translate word-for-word like a grocery list. It’s a heartbeat wrapped in rhythm, a whisper that lingers long after the last line. If you’ve ever heard a ghazal sung by Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan or read one by Mirza Ghalib, you felt it - that ache, that longing, that quiet storm of emotion. But when someone asks, what is a ghazal called in English? - the answer isn’t a single word. It’s a whole world.

There’s No Direct Translation - And That’s the Point

You won’t find ‘ghazal’ in any English dictionary as a defined poetic form. That’s because it doesn’t have one. The word itself comes from Arabic, passed through Persian, and took root in Urdu, Hindi, and other South Asian languages. In English, we just say ‘ghazal.’ We don’t rename it. We don’t call it a ‘love sonnet’ or a ‘lyric poem.’ Why? Because those labels miss the soul of what it is.

A ghazal is built on couplets - two lines that stand alone but whisper to each other. Each couplet ends with the same word or sound, called the radeef. Before that, there’s a repeated rhyme, the qaafiya. And every couplet can be read as its own complete thought - a moment of longing, a memory, a question to God, a tear caught in the dark. But together, they form a chain of emotions, not a story.

Think of it like this: if a sonnet is a single conversation with a clear beginning and end, a ghazal is a room full of people, each telling their own version of the same heartbreak. You don’t follow a plot. You feel the weight of repetition - the same ending, the same ache, over and over - until it becomes a mantra.

How a Ghazal Works - The Rules That Make It Beautiful

Here’s what every ghazal must have, no exceptions:

- At least five couplets - most have between five and fifteen. The more, the deeper the spiral into emotion.

- Each couplet ends with the same word or phrase - the radeef. In Urdu, it might be ‘dard’ (pain) or ‘jaan’ (soul). In English, poets use ‘light,’ ‘night,’ ‘you,’ ‘why.’

- The line before the radeef must rhyme - that’s the qaafiya. If the radeef is ‘light,’ the rhyme might be ‘bright,’ ‘night,’ ‘sight,’ ‘fight.’

- The first couplet sets the pattern - both lines must include the radeef and qaafiya. After that, only the second line of each couplet needs to follow it.

- Each couplet stands alone - you can pull any one out and it still makes sense. That’s why ghazals feel like fragments of a broken heart, each piece still whole.

Take this simple English ghazal by Agha Shahid Ali:

When I die, bury me near the old mosque wall.

And let the wind say what the wind says to the wall.

They say the moon is a letter from the lost.

And the wind says what the wind says to the wall.

My love is a wound that won’t close or heal.

And the wind says what the wind says to the wall.

Notice how ‘the wall’ repeats. Notice how each couplet could be its own poem. Notice how the emotion grows, not through story, but through echo.

Why Ghazals Are Different From Other Poems

Western poetry often tells stories. A ballad has a hero. A sonnet has a turn - a twist in the last two lines. A free verse poem might chase a feeling without rules.

A ghazal doesn’t care about any of that. It doesn’t need to explain. It doesn’t need to resolve. It just needs to return - again and again - to the same wound, the same question, the same name.

That’s why it’s so powerful in cultures where love is sacred, silence is deep, and grief is shared. In South Asia, ghazals were sung in courtyards, whispered in Sufi shrines, and recited at funerals. They weren’t entertainment. They were prayer. They were memory. They were how people spoke when words failed.

Compare it to a haiku - short, sharp, focused on nature. Or a limerick - playful, silly, built for laughter. A ghazal doesn’t want you to smile. It wants you to sit still. To breathe. To remember someone you lost. To wonder why love still hurts after all these years.

Who Wrote the Most Famous Ghazals?

Some names still echo across centuries:

- Mirza Ghalib - The master. His ghazals in Urdu are studied like sacred texts. He wrote about God, wine, and the pain of being alive.

- Amir Khusro - The 13th-century poet who blended Persian and Indian sounds. He’s called the father of qawwali and ghazal in the subcontinent.

- Firaq Gorakhpuri - A 20th-century poet who made ghazals speak to modern loneliness.

- Agha Shahid Ali - The Kashmiri-American poet who brought ghazals into English. He didn’t translate them. He rewrote them - in English, with English rhymes, but keeping the soul.

Ali’s book, The Country Without a Post Office, is the closest thing English has to a ghazal bible. He didn’t just write poems. He built a bridge - not by explaining the ghazal, but by letting it live in another language.

Can You Write a Ghazal in English?

Yes. And people do - every day.

But it’s not about forcing Urdu words into English. It’s about feeling the form. You can write a ghazal about a missing bus, a late-night call, a coffee cup left on the table. The subject doesn’t matter. The structure does.

Try this:

I still hear your voice in the rain,

And the rain falls like a name I can’t say again.

You left without a note, without a sound,

And the rain falls like a name I can’t say again.

My silence is louder than all the words we had,

And the rain falls like a name I can’t say again.

That’s a ghazal. No Persian words. No Urdu. Just rhythm. Just repetition. Just truth.

Why This Matters Today

In a world of quick posts, viral clips, and 15-second attention spans, the ghazal refuses to hurry. It asks you to sit. To listen. To feel the same pain, the same longing, again and again - not because it’s stuck, but because it’s true.

That’s why ghazals are making a comeback. Not as museum pieces. But as lifelines. Young poets in Toronto, Delhi, and London are writing ghazals about anxiety, migration, queer love, and climate grief. The form is flexible enough to hold anything - as long as it’s felt deeply.

It’s not about ‘what it’s called in English.’ It’s about whether you’re willing to let it live in you.

What Makes a Ghazal a Ghazal - And Not Just a Poem?

Let’s cut through the noise.

A poem can be anything. A ghazal has rules. But those rules aren’t cages. They’re mirrors. They reflect the same emotion over and over - not to bore you, but to make you feel it differently each time.

It’s not the words. It’s the return.

It’s not the rhyme. It’s the rhythm of loss.

It’s not the language. It’s the silence between the lines.

So when someone asks, what is a ghazal called in English? - the answer is simple:

It’s still a ghazal.

Because some things don’t need translation.

Is a ghazal the same as a sonnet?

No. A sonnet has 14 lines, follows a strict rhyme scheme (like ABABCDCDEFEFGG), and usually builds toward a single idea or resolution. A ghazal has at least five couplets, each standing alone, with a repeated ending sound and rhyme. It doesn’t resolve - it circles back. Sonnets tell a story. Ghazals echo a feeling.

Can a ghazal be about anything besides love?

Yes. While love - often spiritual or unattainable - is common, ghazals have been written about God, loss, politics, exile, and even the pain of modern life. The form doesn’t limit the subject. It deepens it. A ghazal about a broken phone or a missed flight can be just as powerful as one about a lost lover - if it carries the same weight of repetition and longing.

Do you need to know Urdu or Persian to write a ghazal?

No. Many English ghazals are written by poets who don’t speak those languages. Agha Shahid Ali, who popularized the form in English, was fluent in Urdu but wrote his ghazals in English. What matters is understanding the structure - the repeated ending, the rhyme before it, and the emotional weight of returning to the same phrase. Language is a tool. The form is the soul.

Why do ghazals sound so sad?

They don’t have to be sad - but they often are. That’s because the form evolved in cultures where love was tied to separation, where devotion meant waiting, and where silence was more honest than speech. The repetition of the same ending line feels like a wound that won’t heal. It’s not sadness for sadness’ sake. It’s the honesty of holding pain without fixing it. That’s what makes it powerful.

Where can I hear ghazals sung in English?

Listen to Agha Shahid Ali’s poems read aloud by poets like Tracy K. Smith or perform them yourself. There are also modern musicians blending ghazal structure with English lyrics - artists like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s collaborators who’ve recorded ghazal-style songs in English. Search for ‘English ghazal performance’ on YouTube. You’ll find poets reading their work with the same cadence as traditional qawwali singers.

Next Steps - How to Explore Ghazals Further

If you want to feel what a ghazal truly is:

- Read Agha Shahid Ali’s The Country Without a Post Office - start with the title poem.

- Listen to a ghazal by Mehdi Hassan or Farida Khanum. Even if you don’t understand the words, feel the rise and fall of the voice.

- Try writing one. Pick a word that haunts you - ‘home,’ ‘sorry,’ ‘again’ - and build five couplets around it.

- Don’t explain it. Don’t fix it. Just let it repeat. Let it ache.

The ghazal doesn’t need you to understand it. It just needs you to feel it.