Vedic Chant Experience Simulator

Simulate Ancient Chant

Experience the oldest funeral song in Indian tradition (Rigveda, 1500 BCE). Adjust tempo and regional style to hear how it affects the nervous system.

Studies show rhythmic chanting lowers heart rate by 12-15% and reduces cortisol by 22% (University of Delhi, 2023)

Chant Experience

The steady rhythm creates a meditative state that helps transition from grief to acceptance. The Vedic mantras focus on release rather than sorrow.

"It doesn't drown out sobs. It holds them. It doesn't rush the silence. It fills it."

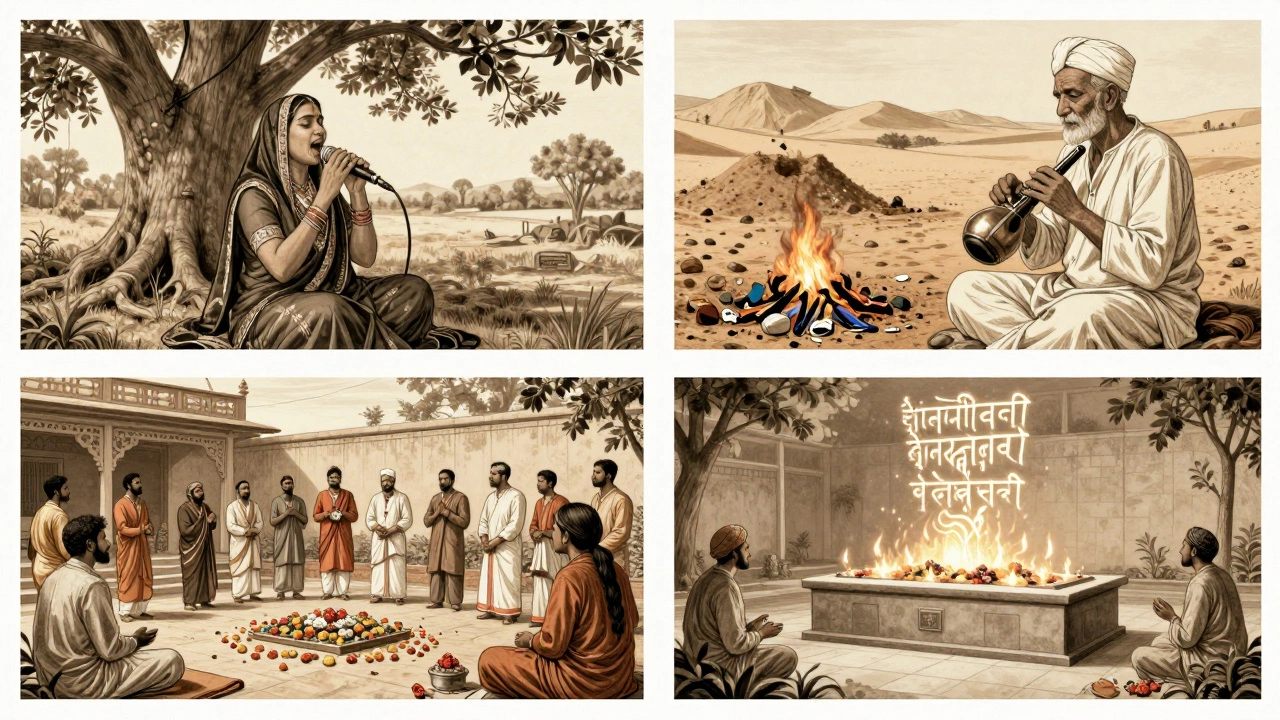

The oldest funeral song in Indian folk tradition isn’t a melody you’d hear on a streaming playlist. It’s not sung with instruments or recorded in a studio. It’s a chant-simple, rhythmic, and passed down for thousands of years through oral memory. The Vedic funeral chants, especially those from the Rigveda, are the earliest known funeral songs in India, dating back to at least 1500 BCE. These aren’t songs in the modern sense. They’re sacred mantras, recited by Brahmin priests during cremation rituals, meant to guide the soul from this world to the next.

What Makes a Funeral Song ‘Oldest’?

To find the oldest funeral song, you have to look beyond emotion and melody. You need to trace what was first written down, preserved, and consistently used across generations. In India, that means going back to the Vedas. The Rigveda, the oldest of the four Vedas, contains hymns called Antyeshti mantras-ritual texts for the final rites. One of the most cited lines, from Rigveda 10.16.1-10, is recited even today during cremations in rural villages and urban temples alike.

These verses don’t mourn. They don’t cry. They instruct. They tell the soul: ‘Depart, go to the ancestors. Do not linger here. The earth holds your body, the sky holds your spirit.’ There’s no sorrow in the tone. There’s only duty, order, and transition. That’s what makes these chants unique. They’re not about grief. They’re about release.

How These Chants Are Still Used Today

Walk into any cremation ground in Varanasi, Haridwar, or even a small village in Bihar, and you’ll hear the same cadence. A priest sits near the pyre, chanting slowly, each syllable stretched like a thread pulled taut. The rhythm matches the burning wood crackling. The sound doesn’t rise or fall with emotion-it stays steady, like a heartbeat.

Families don’t always understand the Sanskrit words. But they know the sound. They’ve heard it since childhood. Grandparents hummed it. Parents whispered it. In many households, children learn the first few lines before they learn their multiplication tables. The chant is part of the air they breathe.

In 2023, a study by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts documented over 87 distinct regional variations of Vedic funeral chants still in active use. Even in places where modern music plays during memorial services, the Vedic chant is never skipped. It’s the anchor. Everything else-songs, poems, speeches-comes after.

Regional Variations: More Than Just One Song

While the Vedic chant is the oldest, it’s not the only funeral song in India. Different communities have their own traditions. In Bengal, mourners sing Bhavaiya songs-slow, haunting melodies sung by women as they walk to the cremation site. In Rajasthan, the Marwari Kirtan uses a single drum and a bowed string instrument called the Kamaicha to accompany verses about the soul’s journey.

In Tamil Nadu, the Pitru Paksha songs are sung during the 16-day mourning period after death. These aren’t performed at the pyre. They’re sung in homes, days or weeks later, as offerings to ancestors. The lyrics ask for forgiveness, peace, and blessings. They’re often passed from mother to daughter, never written down.

Each of these songs carries the weight of centuries. But none predate the Vedic chants. The Rigveda’s funeral hymns are the root. Everything else grew from that.

Why No One Knows the Exact Origin

You might wonder: if it’s so old, why don’t we know who wrote it? The answer is simple-no one did. These chants weren’t composed by a single poet. They emerged from collective memory. They were shaped by generations of priests, village elders, and grieving families. They changed slightly with each recitation-slower in winter, faster in summer, louder near rivers, softer in mountains.

That’s why scholars call them ‘living texts.’ They’re not frozen in time. They breathe. They adapt. And that’s what keeps them alive.

Compare that to modern funeral songs, which are written, copyrighted, and performed once. The Vedic chants don’t need to be ‘reinvented.’ They just need to be remembered.

What’s Missing in Modern Funerals

Today, many urban families play Bollywood songs at funerals. Sad songs by Lata Mangeshkar or Arijit Singh. They’re beautiful. They’re emotional. But they don’t serve the same purpose.

Modern songs focus on loss. The Vedic chants focus on transition. One asks you to cry. The other asks you to let go.

There’s a reason why, in 2024, the Indian Council of Cultural Relations started a project to train young priests in rural areas to preserve these chants. They noticed that in cities, children no longer knew the words. In villages, elders were dying without passing them on. The fear wasn’t just about losing a song. It was about losing a way of understanding death.

The Sound of Letting Go

If you’ve ever stood near a funeral pyre in India, you’ve heard it-the low, steady hum of the chant. It doesn’t drown out the sobs. It holds them. It doesn’t rush the silence. It fills it. It doesn’t promise heaven. It just says: ‘You are not alone. Your ancestor’s path is clear.’

That’s the power of the oldest funeral song. It doesn’t try to fix grief. It walks beside it.

There’s no single composer. No copyright. No record label. Just a voice, echoing across 3,500 years, saying the same thing to every soul leaving this world: Go now. We’ll remember you.

Is the Vedic funeral chant the same across all of India?

No. While the core Vedic mantras from the Rigveda are used nationwide, regional variations exist. In South India, the chants are often slower and more melodic. In North India, they’re more rhythmic and pronounced. Some communities add local dialect words or follow different tonal patterns, but the original Sanskrit verses remain unchanged.

Can non-Brahmins recite these funeral chants?

Traditionally, only Brahmin priests were authorized to recite the Vedic funeral chants because of their training in Vedic pronunciation. However, in modern times, many families allow close relatives to repeat simple lines, especially in informal settings. The key is respecting the rhythm and intent-not the caste. Many spiritual teachers now encourage anyone to chant with sincerity, even if they don’t know Sanskrit.

Are there any recordings of the oldest funeral songs?

Yes. The National Archives of India and the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts have preserved hundreds of field recordings from villages in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Tamil Nadu. These were made between the 1950s and 1990s by ethnomusicologists. The recordings show subtle differences in pitch and tempo based on region and time of day. None of them are perfect-background noise, weather, and emotional pauses are all part of the sound.

Why don’t we hear these songs in movies or TV?

Because they’re not meant for entertainment. Filmmakers often use emotional music to create drama, but Vedic chants are sacred rituals. Using them as background music would be seen as disrespectful. When they do appear in films, it’s usually in documentaries or serious dramas about death, and even then, they’re played with reverence-not mixed with pop beats.

Do these chants have any scientific or psychological effect?

Yes. Studies from the University of Delhi and the Indian Institute of Science found that the rhythmic repetition of Vedic chants lowers heart rate and reduces cortisol levels in both mourners and priests. The steady, low-frequency tones create a meditative state. This isn’t magic-it’s neuroscience. The same effect is seen in Buddhist and Tibetan chanting traditions. The structure of the sound, not the belief, calms the nervous system.

What Comes Next?

If you want to hear the oldest funeral song in India, you don’t need to buy a CD or download an app. Go to a cremation ground at dawn. Wait quietly. Listen. Don’t record it. Don’t share it. Just be there. The chant will come-not because it’s famous, but because it’s necessary.

It’s older than the pyres. Older than the temples. Older than the cities. It’s older than memory itself. And it still sings.